Missives to the Future: On Commit Messages and Maintainability

— Git, software engineering, maintainability — 8 min read

2021 Update

I'm now using Conventional Commits. You should too. Read on to find out why.

My team works on tools to streamline civilian HR processes in the Canadian Department of National Defence. Every week, one team member hosts a learning session to teach everyone about some topic related to our work. This week, I'm giving a talk on the importance of Git commit messages, so I thought I'd write a blogpost about it too. As I mentioned in a previous post, I'm a big fan of Joel Chippindale's talk and blogpost about "telling stories through your commits". My talk largely builds on his post in the hopes of convincing readers of the value of good commit messages, not only on the technical side, but also on the business side.

Why we write code

Have you ever looked at a line of code and wondered:

- What (on Earth) was the previous dev thinking?

- I've tried to understand how this works and I can't - is there someone I can ask about this?

- This line should obviously be done in $OSTENSIBLY_BETTER_WAY, but why wasn't it?

These questions, which inevitably arise in any developer's mind when working with others, hearken back to the philosophy of programming itself. We don't write code for the machine - we write it for other developers. Let me repeat that. We don't write code for the machine - we write it for other developers. What does this really mean?

One of the first lessons in any undergrad intro course to Java, C, or any compiled language is that the human-readable source code is first compiled into a machine-readable format, then executed. This process indicates some fundamental truths:

- The machine-readable format is not necessarily human-readable.

- The machine-readable format is somehow "better" for execution than the human-readable format. (This is for reasons of sheer speed and other optimizations that can be applied via compilation.)

- There is some intrinsic value in keeping the long-lived version of the code human-readable.

It's the third truth that's most interesting to our discussion. Rare is the line of code that's last seen by human eyes as it's written. In fact, it's fair to say that almost every line of code costs time at least twice: first when it's written, and once again every time it's read.

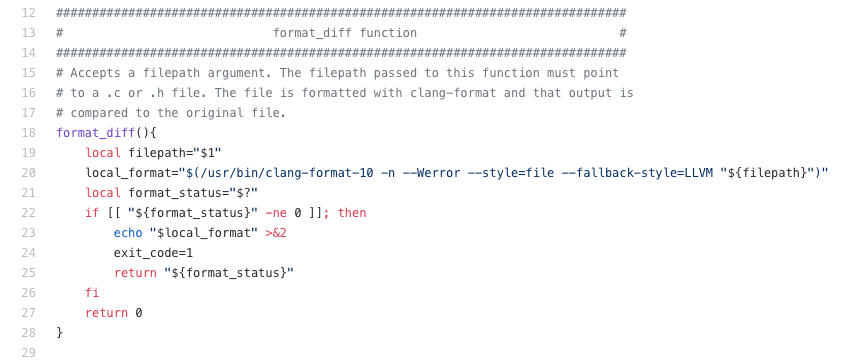

When we write code, we (hopefully) intersperse it with comments to help explain how it solves the problem at hand. For example, I've included a comment preceding a Bash function for capturing and returning the exit status of clang-format on a C file:

But what about the what and the why of our code? These are essentially our thoughts on the code we're writing - how can we save a snapshot of these thoughts along with our code?

Enter version control

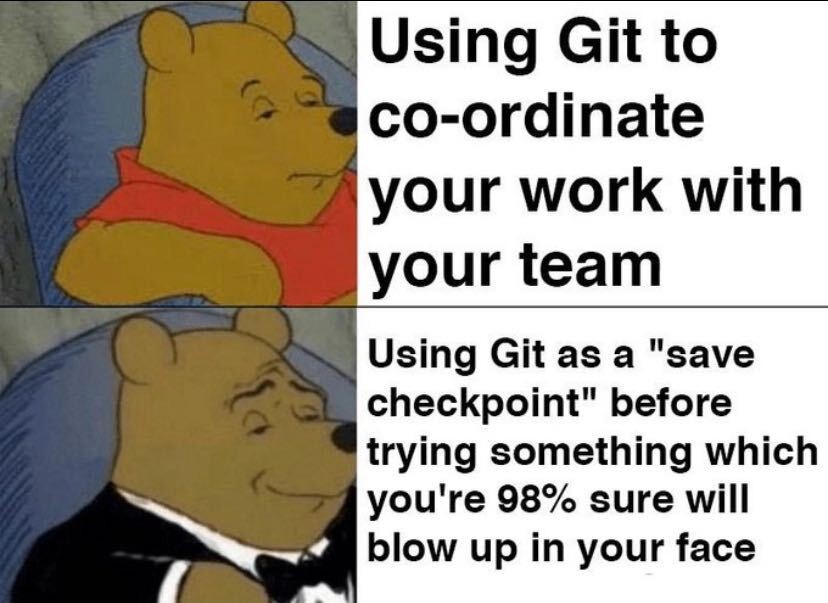

Fortunately, we have a wonderful tool called Git for version control. But why do we use version control, other than as a fallback in case you bust the build?

When we're collaborating with a team, it is critical to our work to have a consensus of the how - everyone must be on the same page with our repository source code. Git is a version control system that consists of chains of commits that tell the shared history of our codebase. Each commit is a hashed object containing:

- a parent commit hash, telling us the ancestry of this point in the code history

- the diff, which is essentially a transformation matrix on the previous state (parent commit) of the code, telling us how this state of the code is reached

- a timestamp, telling us when the change was made

- the commit author, telling us who made the change

- and of course, the commit message, which (ideally) tells us what was changed and why it was changed.

It's worth noting that 4 out of 5 of these attributes are autogenerated by Git, with the last being left up to the commit's author. So how can we use this shared history to bring everyone to a consensus with the what and the why of our code?

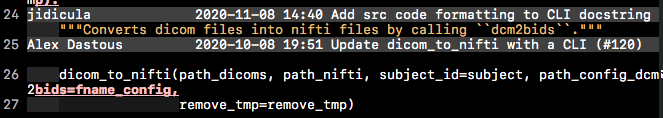

There's a brilliant builtin feature in Git called blame - it tells us, line by line, what commit (and author) is responsible for changes in each line, hence its name. Here's what the blame view looks like in the Magit plugin for Emacs:

This feature, like many things in the software development world, can be described as garbage in, garbage out - a kinder classification would be "you get out what you put in". So how do we make sure we invest real quality into this process to truly leverage the power of this feature?

The 7 rules for commit messages

Credit to Chris Beams

- Separate subject body with a blank line.

- Limit subject line to 50 characters.

- Capitalize the subject line.

- No ending punctuation in the subject line (to save space).

- Use the imperative mood (not past tense!)

- "This commit will [your title]" is a good way to check if the tense is correct.

- Wrap the commit body at 72 chars (terminal-friendly!).

- Body contains what and why, not the how (the diff has this already).

These are a lot of things to remember, but following these guidelines even roughly can dramatically ease code-spelunking done by our colleagues (or us, 6 months into the future). Fortunately, Git has another feature to help us not have to remember these things every time: commit message templates.

1[type][module] TITLE 50 CHARS2types: chore, docs, feat, fix, refactor, style, test3Resolves [issue](4https://linktoissue)5Related to [issue](6https://linktoissue)7

8**Why this change was necessary**9

10

11**What this change does**12

13

14**Any side-effects?**15

16

17**Additional context/notes/links**This template is shared publicly in my dotfiles repo.

To use a template, we just have to save it to a textfile, then modify our git config, either globally in ~/.gitconfig, or for the relevant repo in relevant-repo/.git/config:

1[commit]2 template = ~/path/to/commit-messageA workflow for better commit messages

It's very rare to get a fix right on the first try - often you have a few cracks at a problem before you get it ready for pushing to remote.

We can use the amend feature to modify our commit message as needed. Note that if you use this workflow while pushing intermittently to remote (GitHub), you'll need to force-push at some point.

- Make your first changes.

- Stage your changes with

git add. - Commit your changes (no

-mflag!!!). - Write your commit message in the pop-up editor, save, close.

- Go make some more changes.

- Stage your new changes.

- Run

git commit --amend - Modify message as needed. Save and close the editor.

- Repeat Steps 5-8 as needed.

There are other options too, where we can just make a new commit for each subsequent change, then do a cleanup on our local branch with interactive rebasing to modify local commit history and squash related commits. This Git feature in itself deserves a blogpost of its own, so I won't go into it here.

So with that, we've gone into the nitty-gritty details on how to include better commit messages, and dabbled a bit in rewriting local history too. If I've already convinced you on Git commit messages, that's great! Go forth and write great shared histories. If not, keep reading...

Unlocking technical value with Git commit messages

Most of the technical value unlocked lies in the git commands that we can leverage to better understand code history

git blame: as mentioned before, we can see the commits that changed a line of codegit log: see all repository commitsgit log --grep="commit msg contents": search repository commits for messages matching your grep patterngit log -S "diff contents": search repository commits for diffs containing your grep pattern

Unlocking business value with Git commit messages

Remember those 3 questions from the beginning of this post?

- What (on Earth) was the previous dev thinking?

- I've tried to understand how this works and I can't - is there someone I can ask about this?

- This line should obviously be done in $OSTENSIBLY_BETTER_WAY, but why wasn't it?

What's the cost of diving into a problem without having the answers to those questions?

In the best-case scenario, our first fix is correct. We've shot from the hip and we've hit our target. We commit our changes, push our commits, and make a PR. Our reviewer approves, the fix is merged, and we all move onto the next thing.

In the worst case, you probably have to dig to understand what data is changing where and why, which may not be immediately apparent if you're new to the framework or the specific codebase. Or, a seemingly easy fix actually blows up something else when it's done, and 1 story point becomes 3 as you handle tech debt. Finally, the worst of the worst cases: an easy fix ostensibly works and introduces a regression silently.

Let's think a bit more deeply about the worst case. If we can lessen its frequency, our task estimation improves. Better estimation makes our velocity not only higher, but more accurate. A more accurate velocity and task estimation means we can make timeline commitments to our stakeholders that are easier to keep.

Unlocking this value requires a shift in mindset about commit messages. They are not an afterthought - these messages have the potential to be a form of living documentation for our peers. We must strive to ensure that our commit messages can answer those 3 inevitable questions.

Wrap-up

My call to action for you is to commit to writing messages that add value to the code, for the sake of yourself, your colleagues, and your stakeholders.

Questions? Comments? Write to me at [email protected].

PS: It also makes code review easier.